The History of an Atashgah rooted in the time of the Sassanid’s

In the Absheron peninsula of Azerbaijan, there are many places where the fire comes up from the underground. The earliest mentions of this phenomenon were noted by Priscus in 5th century, by Al-Istakhri and Mas’udi in the 7th-10th centuries. Zoroastrians lived in the Transcaucasia from the Achaemenian times and worshiped these forever burning flames and built the fire temples. One of these temples is called Atashgah (“Place of Fire”) and survives to our days in the Surakhane village, 15 km far from Baku.

- Eternal fire

Centuries passed. In the Middle Ages, trade and the Silk Road connected Hindu merchants from the Punjabi city of Kangar with an abandoned Zoroastrian temple in Surakhane.

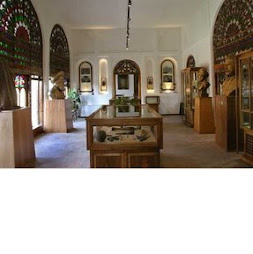

- The guest room

- So called balakhaneh (بالاخانه) is placed above the entrance of the complex of the temple Atashgah.

Since the sixteenth century, Hindus travelled here on pilgrimage. The German traveller Kaempfer (Kämpfer), who visited Atashgah in 1683 mentioned that Hindus began to find the permanent settlements near the Fire Temple. The earliest constructions near the temple were stables, which were built in 1713.

During the 18th century, around the sanctuary there were chapels, cells and a caravanserai.

- Chahar-Taqi

- Atashgah, view from balakhaneh. Above the arch chahar-taqi (چهارطاقی) mounted stove of merchant Kanchanagar. Trident trishul is in the upper part.

- Fire Temple Atashgah with a “small” fire (at the left). In the background — the cells.

- The courtyard of the Fire Temple complex

- At right is the balakhaneh (بالاخانه).

In the cells of the walls are carved inscriptions of the Indian letters Nagrik, Devanagari and Gurmukhi. From the tablets with inscriptions of verses (“Shlokas”) it is clear that the Hindus used Atashgah as a temple of the Hindu goddess of fire Jvalaji. Also, at one of the plates there is an inscription in the Sikh Punjabi language.

According to de Chardin, the Fire Temple in Surakhane during the 60’s period of the 17th century was visited by Zoroastrians. This confirms the Persian handwriting Naskh (نسخ) inscription over the entrance aperture of one of the cells, which speaks about the visit of Zoroastrians from Isfahan:

- The Persian inscription

- The Persian inscription above the entrance to one of the cells: آتشی صف کشیده همچون دک جیی بِوانی رسیده تا بادک سال نو نُزل مبارک باد گفت خانۀ شد رو سنامد (؟) سنة ۱۱۵٨

ātaši saf kešide hamčon dak

jey be vāni reside tā bādak

sāl-e nav-e nozl mobārak bād goft

xāne šod ru *sombole sane-ye hazār-o-sad-o-panjāh-o-haštom

Fire worshippers stand in line, like naked (trees?)The 1158 year corresponds to 1745 AD. Van is implied as the Shirvan region or Bhagavan. The word Badak is used as a diminutive of Badkube (بادکوبه) — the name of Baku. (The name of Baku in the sources of the 17th and 18th centuries was Bad-e Kube. It was written as a Bad-e cubed). At the end of the reference is the constellation of Sombole (سمبل) which is Virgo, the sixth month of the Zoroastrian calendar and the modern Shahrivar (شهریور) month (August-September). In the name of the month the master mistakenly shifted the “l” and “h” at the end of the word. According to Zoroastrian Qadimi calendar New Year in 1745 AD was in August (now Iranian Zoroastrians use Fasli Calendar with Nowruz in March).

Isfahani came from Vani to Badak

«Blessed the lavish New Year», he said

The house was built in the month of Ear in 1158nd year.

Very interesting is the use of words in the inscription “jey” (جی, “isfahani” — اصفهانی), “dak” (دک), “sad” (ساد) and the name of Baku — Van (Bhagavan) and others. Among the remaining inscriptions on the territory of Transcaucasia’s epigraphic monuments such words cannot be found. Perhaps words of this kind are stored in the language of Zoroastrians in Iran.

This inscription indicates that the Zoroastrians did not forget their fire temple, and through many centuries, continued to visit it, despite the fact that the temple was transformed into a Hindu temple.

According to 1767/68 records in the Punjab district, which included the shopping centre city of Multan, the number of Zoroastrians numbered 465 people. In the fortress of Baku city is preserved a caravanserai called Multan. Perhaps the Zoroastrians of India also visited Baku. The English traveller James Bryce referred to this in 1876. He mentioned that the Parsis of Bombay provided a presence of their superintendent in Atashgah.

The Atashgah interested many prominent people who visited Absheron. Among them we can identify such people as Russian Tsar Alexander II, the orientalists Dorn and Berezin, writer Alexander Dumas père, chemist Mendeleev, artists Vereshchagin and Ivanov, and a French traveller Wieland.

At the beginning of the 20th century the English traveller A. Jackson visited Atashgah, and then he published a slightly different English translation of the Persian inscriptions (Jackson, From Constantinople, pp. 53, 54, picture 2, footnote 2):

A fire has been drawn up like the array of a mountain,In 1855, with the development of oil and gas industries, there was built the first oil and gas plant, and natural lights began to weaken. In 1883 the last Hindu priest went to India.

Who can reach up to its crest?

«May the New Year of the abode be blessed»

He said The house has become radiant (? lit light-spear) from it.

Interesting information about Zoroastrian from Baku mentioned by Karaite Abraham Firkovich in his Abne Zikkaron. He wrote about his meeting in Darband in 1840 with fireworshiper from Baku. Russian officer mistakenly introduced the fireworshipper to Firkowicz as the “Bramin”. Firkowicz asked him: «Why do you worship fire?» Fireworshiper replied that they do not worship fire at all, but the Creator, which is not a person, but rather a “matter” (abstraction) called Q’rţ’, and symbolized by fire. Term Q’rţ’ (“kirdar”) means in Pahlavi and Zoroastrian Persian “one who does”, “creator”.

In 1925, at the invitation of the Society for the Survey and Study of Azerbaijan, the famous Bombay Zoroastrian scholar and professor J. J. Modi visited the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. Modi claimed that in the ancient Parsi texts there are references about fire temples on the shores of the Khazar (Caspian) Sea. It should be noted that Modi was unable to read the Persian inscription in the Atashgah and did not see in its architecture of Chahar-tags (چهارطاقی), a specific feature of a fire temple of the Sassanid period. He believed that the Atashgah was exclusively a Hindu temple, and the name of the village Surakhane translated as sho’le-khaneh (شعلهخانه, “House of fire balls”). During his visit to Baku, Modi spent his time on another surviving Zoroastrian temple — the so-called Maiden Tower (قلعۀ دختر, Giz galasi in Azeri Turkic), which he called Atashkade (آتشکده) and rightly considered one of the ancient temples of fire.

In 1975, after restoration work, the Atashgah was opened to the public as a branch of the State Historical and Architectural Museum “Shirvanshah’s Palace”. Fires are burning again, and today the Atashgah is both a place of worship and a museum. Now it is one of the most visited monuments, enjoying great attention.

- Religious ceremony

- Religious ceremony of Iranian Zoroastrians in Atashgah directed by Moobed Kurosh Niknam (مؤبد کوروش نیکنام).

هیچ نظری موجود نیست:

ارسال یک نظر