Issue Number 70September 1997

The CIA's destruction of records concerning the 1953 covert action in Iran, first reported in the New York Times on May 29, 1997, provides an occasion in the following three articles to recall a forgotten episode in the history of the CIA collection; to report on a surprising documentary resource for students of US-Iran relations; and to discuss the disputed interpretation of the 1953 covert action itself.

Files for HostagesThe CIA's collection of records on Iran was once the subject of what must be the most extreme declassification proposal ever conceived.

When Iranian revolutionaries took over the U.S. embassy in Teheran in 1979, they seized dozens of hostages whom they wanted to exchange for the departed Shah, so that they could place him on trial. Philip Agee, the former CIA officer who became notorious for his efforts to expose CIA officers under cover, came up with a counter-proposal:

"What other solution would the Iranians accept [besides return of the Shah]? What about the CIA's files on its operations in Iran? Would the Iranians accept a 'files for hostages' deal instead of 'Shah for hostages'?"

"Those files are their history, all the details on how the Agency set up the SAVAK [secret police], trained its officers, supported that murderous institution in every way possible," Agee wrote. (On the Run, pp. 315-24).

"If the Iranians made a 'files for hostages' proposal, the pressure on [President] Carter [to release the CIA files] might be strong and grow. And if he did give up the files, that would be the end for the CIA."

In the midst of the hostage crisis, Agee telephoned the embassy in Iran and made his proposal, which was in fact submitted to the Revolutionary Council for consideration. Fortunately-- since CIA had already destroyed many of the early documents-- the proposal was rejected after a few days.

The Iranians thanked Mr. Agee for his comradely concern, but pointed out that "People in Iran know what the CIA did." Besides, "we already have a collection of the CIA's documents. We don't need any more to learn what the CIA was doing here."

"Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den"Many people will recall that when Iranian revolutionaries seized the U.S. embassy in Teheran in 1979, they acquired a large cache of classified U.S. government documents, some of which had been shredded and painstakingly reassembled, which they proceeded to publish. What no one seems to have noticed, however, is that they never stopped publishing!

By 1995, an amazing 77 volumes of "Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den" (Asnad-i lanih-'i Jasusi) had been collected and published by the "Muslim Students Following the Line of the Imam" (Center for the Publication of the U.S. Espionage Den's Documents, P.O. Box 15815-3489, Teheran, Islamic Republic of Iran, tel. 824005). Each volume contains original documents along with Farsi translations and, for no extra charge, an inflammatory introductory essay.

"The seizure of the embassy meant that the radicals gained access to a veritable treasury of secret and confidential documents covering some thirty years of Iranian history," wrote Amir Taheri in Nest of Spies (Pantheon Books, 1988). "They reveal the techniques of superpower diplomacy first hand and on a day-to-day basis." Although Taheri's book was not particularly well- received by reviewers, it seems to be the only book-length study to exploit the Iranian collection, or at least the 58 volumes that had been published as of 1987. The documents were also rather superficially examined by Edward Jay Epstein in an article titled "Secrets from the CIA Archive in Teheran" and published in Orbis (Spring 1987).

Ironically (not to say Iranically), publication of the documents represents an extraordinary service to scholars and to the interested public, particularly in light of the CIA's destruction of portions of the historical record on Iran.

Although there are a handful of obvious gems, the Iranians' criteria for publication are weak or nonexistent-- they seem intent on publishing everything that they recovered from the embassy, from detailed CIA procedures for handling defectors to a discussion of whether the Boy Scouts of America should plan on attending the 1979 Boy Scout Jamboree in Iran. The indiscriminate character of the collection is both its weakness and its strength.

Along with voluminous embassy cable traffic, CIA intelligence assessments and estimates that remain classified in the U.S., some of the documents in the Iranian collection are of a sort that would never be released by the CIA, since they contain detailed information on sensitive sources. Indeed, at least one execution of a CIA source is directly attributable to the capture of these records.

But since the documents have already been disclosed, all possible damage has already been done, and the collection offers American readers a unique window on diplomatic and intelligence activity that is completely unobscured by classification constraints.

The Iranian records cannot replace the CIA records of the 1953 coup in Iran that have been destroyed, since they originate overwhelmingly from the late 1970s. But they could add considerably to the history of that later period.

Professor Warren Kimball, chairman of the State Department Historical Advisory Committee, told S&GB that "These documents may be worth considering as a source for reconstructing American foreign policy toward that region, particularly if other records remain classified or do not exist."

Some, though not all, of the volumes are available at the excellent Iranbooks in Bethesda, Maryland.

Reconsidering the 1953 "Coup" in IranHistory abhors a vacuum, and so the void created by the classification (and later destruction) of CIA records concerning the 1953 crisis in Iran has been filled with partial truths and fabrications that have endured despite persuasive scholarly rebuttal.

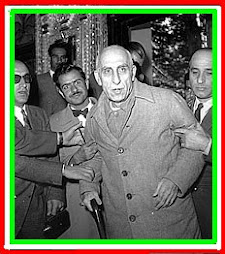

Thus, for example, "In 1953 Kermit [Roosevelt] and a few fellows manipulated that crowd which toppled [Iranian Prime Minister Muhammad] Mossadegh without any trouble at all," according to former CIA officer David Atlee Phillips' book The Night Watch.

American covert action in Iran during the 1950s is "something the whole world already knew about," according to a Washington Post editorial (8/17/97). The CIA's destruction of documents concerning its role in the 1953 coup in Iran is "a self-accusation," wrote Theodore Draper in the New York Review of Books (8/14/97). "The CIA had much to hide and decided to do it in the most effective way-- by destroying the official record."

But what the whole world already knew may be mistaken, and what the destroyed CIA records might have shown in this case is not how much the Agency had to hide, but just how little the CIA actually had to do with the removal of Iranian Prime Minister Mossadegh from power in 1953 and the restoration of the Shah to his throne.

The CIA and the enemies of the Shah both had an interest in exaggerating the role of the Agency in the 1953 crisis. Asserting a "victory" in Iran helped the CIA to establish its competence, and to demonstrate its apparent ability to shape events in foreign lands. At the same time, by portraying the Shah as a American puppet who was returned to power by CIA dirty tricks, the Shah's enemies sought to undermine his legitimacy.

In reality, however, by 1953 the Mossadegh regime was already unstable, having lost the support of many elements of Iranian society, from the military to the mullahs. "Overthrowing Mossadegh had been like pushing on an already-opened door," wrote Barry Rubin in Paved With Good Intentions: The American Experience and Iran (p. 89).

Nevertheless, "the belief that the United States had single-handedly imposed a harsh tyrant on a reluctant populace became one of the central myths of the relationship, particularly as viewed from Iran," observed Gary Sick in his definitive work All Fall Down: America's Tragic Encounter with Iran (1985, p. 7).

"According to the yarns woven by the CIA on the one hand and anti-shah elements on the other, the entire August [1953] uprising had been an American enterprise whose success was solely due to CIA money and intrigue," wrote Amir Taheri, who was editor of Iran's largest daily newspaper from 1973 to 1979.

"What actually happened was not the successful conclusion of a conspiracy but a genuine popular uprising provoked by economic hardship, political fear and religious prejudice," Taheri wrote in his 1988 book Nest of Spies (p. 36). He goes so far as to argue that "[E]xamination of the mass of evidence now available proves that the CIA and its former agents deliberately exaggerated their role in those events." He notes that out of the $1 million allocated for the CIA's Operation AJAX (supposedly "to wash the Red out of Iran"), no more than $75,000 was actually used for the purpose of mobilizing crowds in Teheran.

In any case, distorted history can easily overwhelm a secret truth, and the myth of the CIA's overthrow of Mossadegh, propagated notably by CIA officer Kermit Roosevelt in his 1979 book Countercoup, is no less consequential for having been, in important respects, inaccurate and misleading. (Intelligence scholar Hayden B. Peake told S&GB that the first edition of Roosevelt's book was modified under British pressure and reissued to exclude certain references to British intelligence.)

The perceived success of the CIA in toppling Mossadegh inaugurated a fascination with covert action that continues to this day, with the Senate Intelligence Committee boasting of "new investments" and "aggressive efforts" in covert action for fiscal year 1998. The (suppressed) truth of the historical record about Iran and the grotesque failures of covert action-- from the Bay of Pigs to the very latest fiasco in Iraq-- have been unable to dislodge the belief in its efficacy that originated with the Iran coup.

Though Roosevelt's Countercoup is pompous and self- congratulatory ("You owe me nothing at all," he says he told the Shah, "except... thanks"), and filled with unlikely detail, he himself recognized that the Iran action was a special case, and not a model that could be readily adopted elsewhere.

"If we, the CIA, are ever going to try something like this again, we must be absolutely sure that the people and the army want what we want. If not, you had better give the job to the Marines," he warned government officials. Writing 25 years later, he lamented that his warning had not been heeded.

More harshly, Amir Taheri argues that "The extravagant claims made by the CIA about Operation AJAX in later years were to have disastrous effects for future relations between Iran and the United States.... Besides casting doubt on the shah's legitimacy, the CIA claims... helped create an anti-American sentiment that had not previously existed in Iran.... The super-spies who some years later went around claiming medals for their supposedly heroic role in Operation AJAX deserved no such rewards. Unknowingly, they did a great disservice both to Iran and to the United States."

The most measured assessment appears to be that offered by Barry Rubin: "It cannot be said that the United States overthrew Mossadegh and replaced him with the shah. The CIA merely provided minimal financial and logistical aid for Iranians to do so."

Y: Israel's "High Priest of Secrecy""He has extraordinary power, for someone who is so little known," said one Israeli.

Yechiel Horev is the head of the most secretive branch of Israel's intelligence and security apparatus, called by the unwieldy name of Memuneh al habitachon beMaarechet haBitachon (MLMB) or, approximately, "the office in charge of security in the security system."

The MLMB has diverse responsibilities that extend throughout Israel's sizable military establishment, including information security, physical security, industrial security, counterintelligence, and more. Though the MLMB is practically unknown to the general public in Israel, its name "instills fear" within Israel's military-industrial-nuclear complex, according to a detailed article by Yossi Melman entitled "The High Priest of Secrecy" that appeared in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz (7/25/97).

Yechiel Horev "is kind of a 'square', with stubborn principles," said a former official of the Shin Bet security service quoted by Melman. "Despite his relatively young age, he belongs to the old generation of those for whom the security discipline became their total philosophy."

But, notes Mr. Melman, at a time when the names and pictures of the head of Israel's Mossad (foreign intelligence), Shin Bet (internal security), and Aman (military intelligence) are all published routinely, the identity of Yechiel Horev remains a state secret in Israel. Under Israel's system of military censorship, the press can refer to Mr. Horev, whose name is published here for the first time, only by his first initial Y.

This practice now seems anachronistic to some Israelis. "The situation is absurd and intolerable," Knesset member Ran Cohen, a former chairman of the Knesset subcommittee on the clandestine services, told Haaretz. Mr. Cohen wrote to the Israeli Minister of Defense in July urging disclosure of Mr. Horev's name. He argued that the continued secrecy surrounding the MLMB is inappropriate, and that greater public scrutiny should be permitted. "Sunlight is the best disinfectant," he wrote, paraphrasing Justice Brandeis. But the Ministry of Defense was not impressed and the request was rejected.

New Releases

Even though "progress [on declassification] throughout the executive branch has been uneven and, in some agencies, very slow to get started," a staggering 196 million pages were declassified last year under the provisions of executive order 12958, according to the 1996 annual report of the Information Security Oversight Office.

On the other hand, several volumes of official U.S. history "now stand in never-never land" because of the unwillingness of CIA to declassify its historical records, according to the 1996 annual report of the State Department Historical Advisory Committee.

Secrecy & Government Bulletin is written by Steven Aftergood and published by the Federation of American Scientists.

The FAS Project on Government Secrecy is supported by grants from the Rockefeller Family Fund, the Greenville Foundation, the Stewart R. Mott Charitable Trust, and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

var gaJsHost = (("https:" == document.location.protocol) ? "https://ssl." : "http://www.");

document.write(unescape("%3Cscript src='" + gaJsHost + "google-analytics.com/ga.js' type='text/javascript'%3E%3C/script%3E"));

var pageTracker = _gat._getTracker("UA-3263347-1");

pageTracker._initData();

pageTracker._trackPageview();

_uacct = "UA-3263347-1";

urchinTracker();

FAS Homepage Secrecy S&G Bulletin Index Search Join FAS